Spencer Pryse

Gerald Eric Spencer Pryse (1881-1957)

Pryse was instrumental in changing the view of lithography as that of a fine art, mainly thanks to his publication The Neolith, which was later to be taken over by the Senefelder Club. This showcased the talents of artists, as well as poets and essayists. He was orphaned at a young age (http://www.campbell-fine-art.com/cat_works.php?art=240), denied his inheritance and due to this was unable to afford the oil painting training he truly wished for; it was because of this that he chose to embark on lithography, which was a cheaper method of printing. His first exhibit was the 1907 Venice International Exhibition and from there he would go on to create war posters, posters for the British Red Cross, as well as for the Underground Electric Railways Company of London.

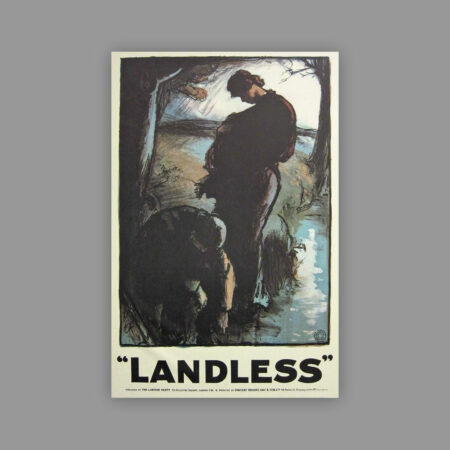

His ideology was very much in line with the socialist ideas of the Labour Party, and are reflected in his three propaganda posters. Despite the anti-war stance held by his party he did in fact serve in the military, as a dispatch rider for the Belgian Army, as well as later being an Official War Artist. He applied for this position many times and was continually side-lined, possibly due to his socialist leanings, but he was finally granted a license in 1917. Many of his sketches were lost in 1918 with the surviving impressions later displayed in a London exhibit, but they too were lost, as they were destroyed in World War 2.

His work as a war artist reflected the scenes he witnessed exactly as he saw them, which was his trademark, which is what we also see in these pieces. A clear story telling of the desperation that had besieged the nation as people lived in squalor, with no hope and no prospects.

In 2014 one of his pieces sold for over $5,000 (source). His work had disappeared for the most part, possibly due to his political affiliations, and it is only in recent years that we have seen his work reappearing in the public eye. The time in history that these works reflect make his art that much more important, as they accurately capture not just a snapshot of the period, but also the plight of the working people.

Showing the single result